This week much of the admissions and enrollment profession will be heading to Columbus, Ohio, for the NACAC Conference. I hope to see many of my colleagues there.

If you listen to conventional wisdom, you’ll frequently hear that you need more data, better data, and–especially this year–more AI. (Just be sure not to mix it up with the steak sauce.)

Are the people telling you this right?

Spoiler: Maybe. But probably not. Or, more accurately, probably not yet.

Let’s jump into Peabody and Sherman’s WayBack Machine to the early 1980’s, when I started in admissions, for a double dose of your daily metaphors. As I’ve told dozens of times, the first time I did a funnel analysis, I did it using index cards (each student was one card), a pencil, greenbar computer printout paper, and a calculator. It was not sophisticated analysis, but in those days (where we had one computer terminal, connected to one computer shared by three colleges), it was all we had: Calculating mean GPA or ACT, or counting enrollment by state was a labor intensive process.

And the travel part of recruitment was very different too, if for no other reason than finding your way around required paper maps, and maybe some notes from another staff member who had visited previously; while that road map could get you to Red Oak, Iowa or Red Wing, Minnesota, small towns didn’t have their own maps, and finding your way around required a little ingenuity.

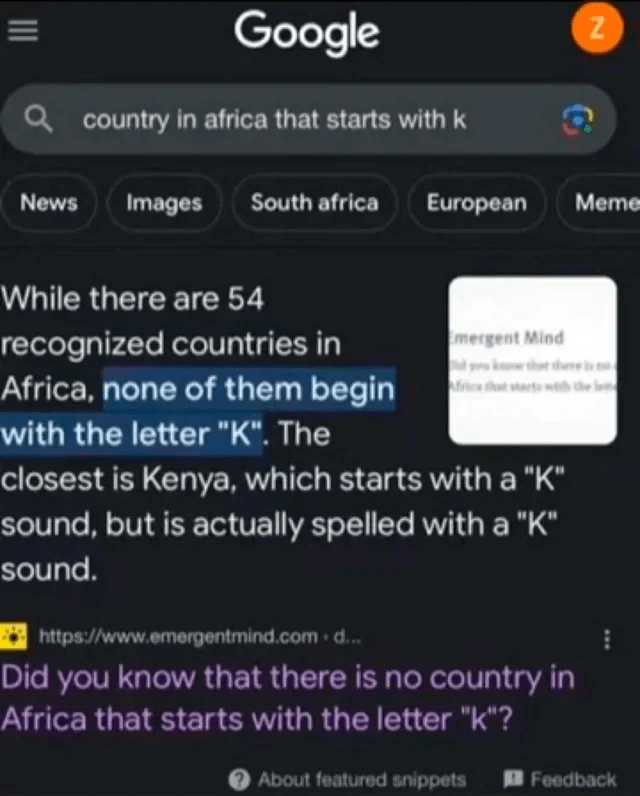

Doing a funnel analysis the hard way, or reading road maps to get you where you wanted to be taught you a lot about data analysis and traveling, that (old man rant alert ahead) you don’t get by running a Slate report or punching an address into Google Maps. The information is there, of course, but there is no discovery that happens along the way. Even pulling down a file and running it through SPSS or Excel, or previewing your route on Street View isn’t the same. If you’ve ever had Google Maps tell you to take two U-turns right after each other, you might know what I mean; you might get where you’re going, but there are clearly better ways. Or, of course, if you’ve ever asked Google’s AI tool which countries in Africa start with the letter K.

Fast forward 20 years. Technology has brought us a long way by the first decade of the 21st century, and I had moved a couple of times by then. I remember a data analyst who prepared a big PowerPoint presentation after analyzing data for the admissions office: The key findings were that students who lived closer to campus yielded at higher rates; students who never visited campus yielded at lower rates; and high-income, highest achieving students yielded at such low rates that you might wonder why you admit them in the first place. None of these, of course, were revelations to anyone who had done the job for a while, even though they were mind-blowing to that analyst: They had uncovered something they didn’t know and were very excited by it. As they should have been.

When looking at information, especially canned, pre-packaged, top line information–whether that comes from an Excel cross tab or the most sophisticated LLM–context is always critical, as is experience with the data. You need to approach these solutions with something Chris Argyris called, “Double Loop Learning” where you don’t just answer a question, but you challenge the assumptions that caused the question in the first place.

My former boss and I call it the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre. It was probably about 2010 or so. We had traveled to our analyst partner to look at applications, admissions, deposits to date, and the model outputs (in those days I think we had something like 700 data points in the files) to see if we were on track to meet our budgeted targets.

We weren’t. We weren’t even close. There was panic in the room. I calmly said, “There is a problem with the data. This is all wrong. This is so wrong it cannot possibly be right.” Ten minutes later, something one of our data people said via a frantic phone call proved I was right. There was a problem with the data we’d sent. Fixing that fixed everything. We made the class. Easily, if I remember.

The answer to our question was not in the output of the model, as most people assumed. It was with the accuracy of the data going into the model.

If you don’t have curiosity, if you don’t wonder why things are the way they are, if you don’t know the data that goes into your models, if you don’t poke back and question the conclusions that are presented to you, more data and AI won’t help you. You’ll be working for them, instead of the other way around.

Yes, you need more data, and you will need to work with AI and bring both into your systems. But unless you first acquire the curiosity and the skills, you’ll be like me sitting in front of the world’s best piano, hoping to play the Goldberg variations.

Discover more from Enrollment VP

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.